|

Have

you ever had a friend or relative die, and wished

you could have kept them at home for

a day or two, to take care of the body yourself

and say your farewells without pressure?

In fact, you can.

Caring

for your deceased loved one at home is simpler

than it may seem, but certain tasks (including

the filing of paperwork) do need to be

done at specific times — see General

Timeline below. Embalming

is usually not necessary, and in most places there

is no legal requirement to make use of a funeral

home.

Post-death

care

may include getting the body from the hospital

or hospice (unless your Death Journeyer

died at home); washing and dressing the

body; cooling it with dry ice or Techni-Ice/Cryopak

blankets; making or buying a simple shroud or

casket, and decorating it as you choose; putting

the body into the casket or shroud; and then finally

transporting it to a crematory or burial ground.

See

Post-death

Care at Home below.

Resources

to support you in post-death care can vary between

provinces/territories. The primary ones

are available at Resources

Pre-Death and Resources

Post-Death. Please check

with your local Hospice or other advocacy groups

to find out what resources (such

as grief counselling) are available in

your area. If you have difficulties,

please contact

us — we may have, or be able to find,

further specific information.

Summary

Overview

of At-Home Post-Death Care and/or Home Funerals

Right

to care for your own dead Most

North Americans — especially urban people

— assume that the law requires that the body

of a deceased must go to a commercial funeral

home shortly after death. In fact,

in most cases, this is not true — families

have the right to care for their own dead until

the body is buried or cremated. Again

— in most cases — you also have the

right to bring the body to your home after your

person has died in a hospital, hospice

or residential care facility. Post-death

care is not that difficult, nor that different

from pre-death care — and most of the documents

needed are available to families from your local

Vital Statistics office.

It

is important to note that

the law allows for multiple options (such

as the rights above) that are not actually

spelt out in it — that is, it does not restrict

such options. Much of

what is considered 'law' in our culture is only

common practice — which then leads to misconceptions

of what is possible and what is not; and even

funeral directors are often misinformed by their

training.

For example, in B.C.,

the only restriction on time of burial or cremation

is that a body cannot be cremated before

48 hours (to allow for investigation

of cause of death, if necessary).

Also, the following statement from the city of

Prince George, B.C., clarifies that: "There

is no law that states a specific time-frame for

burial. The timeline is usually determined

by the need to secure all permits and authorizations,

notify family and friends, prepare the cemetery

site, and observe religious and cultural rituals."

("A

Death in Your Family")

Many

people find that keeping their person

at home and doing the post-death care themselves

(or with the guidance of an

alternative death-care provider) is

a significant last act of loving care. It

allows for the whole of the family (including

children), and their closest friends,

to organize the post-death events according

to what is personally meaningful to them (and/or

the death journeyer). Thus

they can create a personalized continuum between

the pre-death process, and the final burial/cremation

and funeral/memorial. It

can also be considerably less expensive than

using a funeral home -- except for direct

creamtion where the body is moved to the crematorium

immediately after death. |

|

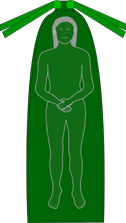

Rolling

the Body in Preparation for Washing the

Back

Rolling

the Body in Preparation for Washing the

Back |

|

|

|

| There

are definitely situations in which delegating

post-death care to a funeral home may be appropriate: |

| |

|

|

It

may be required by, or customary to,

your faith. |

| |

|

|

The

death occurred as the result of a disfiguring

accident, or if the Death Journeyer

died alone and wasn't found for days

afterwards (in which

case the body may have begun to decompose). |

| |

|

|

The

family may wish the funeral held elsewhere

— either where more of them can

attend, or in order for the Death Journeyer

to be buried in the family plot (in

which case, embalming may be necessary

for the sake of transporting the body). |

| |

|

|

There

may not be any suitable home (belonging

to family or friends) in the

area, to bring the Death Journeyer home

to. |

| |

|

|

Or

it may simply be the case that it would

be awkward for any family member or

friend to do the post-death care, because

of family dynamics or their own practical

situation. |

| |

| Further

Notes on preparing for a home funeral: |

| |

|

|

The

body can be brought directly home from

the hospital or residential care facility

— if a family member or friend

is willing to take on post-death care

— but the transfer must be authorized

by the executor, or next-of-kin (if

an executor has not been named). |

| |

|

|

It

is possible that a funeral home facility

— once in possession of the deceased

body — will allow the body to be

taken to the family home for a short

period of time (2-3 days).

However, they might insist on embalming

the body first. In such

a case, the family needs to consider

whether the value of having the body

at home outweighs the carbon-footprint

of embalming. |

|

Funeral

homes who use more ecologically-friendly

products are listed on the Green Burial

Council site under Find

GBC Providers. The

degree of 'greenness' is denoted by

the number of green leaves beside a

listing — graduating from pale

to darker green, with the darker leaves

given to those who offer the most ecologically-friendly

options. |

|

Even

if you have already pre-paid for funeral

arrangements with a specific funeral

home (sometimes called

a 'pre-need' or 'pre-planned' contract),

you may be able to cancel the contract

if you later choose to have a home funeral. It

is likely, however, that there will

be a penalty for doing so; and it should

be clearly written into the contract. Check

your province/territory's Consumer Protection

agency for further clarification of

rights re cancelling contracts, as each

has slightly different rules (see

Consumer Protection agencies for

each province/territory on our Resources

— Post-death page). |

|

(return

to top)

Canadians

can do it at home

It is important that Canadians know that

at-home family-based post-deathcare is a realistic,

accessible, and legal option.

| |

|

|

Especially

with the advent of extensive hospice/palliative

care, more people can die at home with all

the 'comfort care' that the Death Journeyer

requires. Where such care is available,

the palliative-care teams can — within

the person's own home — supply

most of the nursing/caregiving services and

basic medical equipment that would otherwise

be provided in a hospital or hospice. |

| |

|

|

If

the Death Journeyer dies in a hospital,

hospice, or residential care facility, you

have the right to take the body home after

death — although you may need a Permit

for Burial or Cremation, and possibly a

Permit to Transport the Body, with you.

[Note:

The Permit to Transport the Body may also

be known by other names, such as Private

Transfer Permit or Body Transport Permit.

It may not be required

in your province —

to date, we are only aware of such permits

being required in B.C. and Ontario. See

the CINDEA page on Resources

in Canada —

Post-death,

section Legal

Information and Regulations] |

| |

|

|

Washing/dressing

the body is usually fairly simple (instructions

are given in the

Post-death Physical Care (PDF) and videos

below). There are, in fact,

many things done when the Death Journeyer

is still alive (inserting IVs,

changing bandages, caring for dry mouth)

that may not need to be done afterwards. |

| |

|

|

Rigor

mortis usually takes several hours to set

in (2-7 hours), and

relaxes again within about 36-72 hours —

depending on various factors re the deceased's

size/etc. and the environmental conditions. Post-death

care can continue during the early stages

of rigor mortis. |

| |

|

|

A

dead body can be kept at home for 3-5 days,

without significant deterioration, with the

use of fans, air conditioining and dry ice

— or with Cryopak blankets (order

from Cryopak)

which are safer to use than

dry ice. Notably, Cryopak ice blankets are also commonly available in \many large stores, especially during the summer. |

| |

|

|

All

documents and permits are available to families.

[ See

Resources

in Canada —

Post-death,

section Legal

Information,

for govermental and other links for access

to these documents.] |

| |

|

|

As

long as a casket meets some general standards,

you can make it yourself — or buy a standard

cardboard/pressboard one and decorate it according

to your own wishes. There are

casket-building companies who are beginning

to offer ecologically-conscious options —

made from wicker, recycled wood or cardboard,

etc. You also do have the right

to buy a casket from a business other than

a funeral home (for some options,

and blueprints to make your own, see Eco-Friendly

Coffins, Shrouds, and Urn or CINDEA

's Shroud

patterns).

Some cemeteries also accept simple

shrouds (i.e. without a casket

at all) — and for some religions,

shroud-burial is, in fact, a requirement. |

CINDEA has attempted to provide the necessary

information on how to deal with all of the elements

of at-home post-deathcare — on this page,

and on its 'Resources in Canada' pages.

(return

to top)

A

Short History of Post-Deathcare and Funerals

|

Delegating

post-death care to funeral homes

In North America, it has become customary

for professional funeral directors to handle

all care of the body after death, including

the documentation and funeral ceremonies

— so much so that most people believe

it to be required by law. In

fact, in most cases, it is not required

— the primary exceptions being when

|

| |

|

|

the

body needs to be transported a long distance,

(and therefore may need to

be embalmed), |

| |

|

|

non-organic

devices (pacemaker, etc.)

may need to be removed before burial or cremation,

or |

| |

|

|

there

is a question as to the cause of death (in

which case the body needs to be investigated

by a coroner). |

|

Even

in these cases — depending on the specific

circumstances — you do not need to

use a funeral home. For example,

if the body is being transported immediately

and is kept cool, it may not need to be

embalmed to be taken to another city or

province.

Theoretically,

there is no reason why an autopsied body

can't be brought home after the coroner

has closed the body. If

your person's death is likely to

be autopsied, it is

wise to check out the rules of your municipality

or province in advance: and if you are having

difficulty getting clear answers or permission,

please feel free to contact

us — and we will do as much as

we can to help you figure out how to have

your person's wishes granted. |

(return

to top)

|

The

tradition of embalming

Embalming has become

so popular that many people believe it also

to be required by law — which it is

not, except perhaps when the body needs

to be transported long distances. [Note:

in some funeral homes, bodies are embalmed

to "allow" for formal viewing/visitation

—

even though a cremation will happen soon

after the death. However, informal

visitation with no embalming can often be

arranged. Embalming may

be required, if you choose to take the body

home after the funeral home has taken possession

of it.]

Since

embalming can only be done by licensed professionals

in certified facilities, it became common

to assume that a deceased body had to be

moved to a funeral home soon after death,

in order for it to be embalmed. It

is notable, however, that Jewish, Muslim,

Hindu, Bahá'í, and other traditions

forbid embalming — and often require

that the body be buried within 24 hours,

which would preclude embalming in any case.

In many countries, whether or

not the body is embalmed, it is always returned

to the family home — if the death journeyer

died in a hospital or residential care facility

— for the final ceremonies. |

Earth

—

remembrance flower mandala by Elli

Boray

Earth

—

remembrance flower mandala by Elli

Boray

|

|

(return

to top)

All

of these elements became a status symbol —

as family members were encouraged (and

sometimes even intimidated) to choose the

more elaborate services, ornate caskets, prominent

gravesites, and ornamental tombstones (even

if cremated, the ashes may be buried under a tombstone)

— designed to 'prove that they were truly

honouring their loved one'. As

a result, even fairly modest funeral and burial/cremation

services can easily cost as much as $8,000 or

more (especially if buried),

once all of the services are tallied.

(return

to top)

| Denying

the reality of death

Our society has developed

a set of conventional practices intended to

remove death from our consciousness. When

a dead body is moved to a funeral home, it

disappears — although we know it isn't

true, it can be easier to (unconsciously)

believe that our person has simply

gone away on a long trip. If we

were not able to be present at the death or

shortly afterwards to say our final 'goodbyes',

funeral homes may charge $100-$200 for even

a single-person visitation/viewing.

If we do see the body again (at

the visitation or open-casket funeral),

it has been made-up to look like our loved

one is alive and only sleeping.

All of this is actually meant to encourage

us to believe that the death is not entirely

real — that our person's last

breath was not final. |

|

Washing

the Hair

Washing

the Hair |

We

may have contributed our own personal eulogies

at the funeral; but customarily, the main rite

is spoken by the clergy or funeral director —

who may have never known the person that we treasure

so deeply, nor witnessed any of their moments

that are weaving through our minds as we recognize

that these will never be shared again.

Our

person lies in a non-customized casket

— not made by our hands, nor placed there

by us. We may watch the casket being

lowered into the grave — but not cover it

with shovels full of sweat and tears, knowing

that this act is the final 'goodbye'; or watch

it being rolled into the cremation furnace —

but not push the button that ignites the flames

that consume it so finally. [Note:

even watching the casket lowered into the grave

or rolled into the cremation chamber has been

discouraged —

or even disallowed —

but that is changing in recent years.]

(return

to top)

Death

is no longer part of the cycle of life

When we delegate post-death

care to a commercial funeral home, we separate ourselves

from the reality of the death. As a

result, we isolate ourselves from the concept of

death being a sad, but necessary, part of the cycle

of life. We perpetuate the cultural

myth that we (if not other people)

will live forever; and in doing so, fail to face

our own mortality or prepare for our own dying/death.

Also — as so many near-death survivors

have affirmed — when we face death, it significantly

changes the value we put on our daily lives.

|

Moreover,

our grieving can become a private and lonely

affair — uncomfortable to share with

even our closest family and friends, and

hard to commemorate with them in the years

to come. Friends who are not

close relatives may be left wondering whether

it will be acceptable to the family to mention

the death on its anniversary — even

knowing that that acknowledgement might

be intensely meaningful to the family —

for fear of inadvertently offending, if

the reference to the death is unwanted.

And for the close family themselves,

if they did not call their friends together

to share grief at the time the death occurred,

they may feel that they have no right to

do so on following anniversaries either.

The very act of caring

for the body ourselves creates a community

of grieving.

In

effect, our culture (albeit

somewhat inadvertently, since the intention

is actually to protect us) tends

towards encouraging us to continue on as

if the death never happened — and although

not really intending to, as if our loved

one never existed (except,

perhaps, for a tombstone acknowledging where

their body was buried). For

most people, the worst fear about their

eventual death is not the pain and suffering

involved in dying (especially

now that modern medical technology can alleviate

most of that), but the fact that

we will no longer exist — even in the

memories of our dearest friends. |

|

When

you're caring for someone at home you and

your family need support also.... It's

easy to imagine that you're the only one

with such your worries, as we talk so little

about death and dying in our society. Be

assured though that others in your situation

have very similar concerns. It's

just that people don't always have the courage

to talk about them. [From

Virtual Hospice article Dying

at Home — My father would like to die

at home. What can we expect?

]

Toasting

the Death Journeyer

during a home funeral |

(return

to top)

Continuance

of post-death care at home

However — especially

in some rural areas, or in intentional communities

— the tradition of the family caring

for the deceased has continued into the present

day. Particularly in the 1990s,

even urban families began questioning our

cultural funeral customs for a number of reasons:

|

|

Dying

at home helps not just the dying patient,

but society as a whole...more free hospital

beds for patients who can benefit from hospital

services. Additionally, "aggressive,

expensive, painful and futile" care

in hospital is often avoided when patients

are able to die at home. Donna

Wilson, professor of nursing at the University

of Alberta — from the CBC News project

A

Good Death, a co-production with students

from the Graduate Program in Journalism

at Western.

About

25 percent of all health-care costs are

devoted to caring for patients in their

last year of life.... Almost

70 percent of people die in the hospital,

including some in high-tech intensive-care

beds, which cost about $1-million a year

to operate. Many patients fail

to complete advance directives or communicate

preferences.... they could be subject to

costly, invasive treatments they did not

actually want. Lisa

Priest —

November 29,2011 How

much does dying cost Canadians? [from

the Globe and Mail

'end of life' series] |

| |

|

|

Items

and services that weren't necessarily appropriate

(or that didn't fit the values

of the death journeyer or their family)

added to the overall cost. |

|

Given

the demographics of the baby-boomer generation

and their increasing longevity, families became

concerned that personal and health-care funds

might not be available to their children or

grandchildren because funds are used for

|

| |

|

|

a series of what are likely to be unnecessary

treatments, and artificially maintaining lives

beyond any 'quality of life' (it

is estimated that a person uses twice as many

health-care dollars in their last year of

life, as in the whole of their life beforehand)

— and |

| |

|

|

customary,

but unnecessary, post-death services. [Memorial

societies were created to reduce these costs,

and support families to only choose what they

felt was appropriate or necessary from a funeral

home.] |

|

Although

funeral directors are generally caring, compassionate

individuals, they have limits imposed on them

as to what they can offer, in terms of personalized

choices — by law, customary practice,

company policy or their professional association's

standards. |

(return

to top)

Alternative

Death-care providers

As a result, some individuals

— with direct experience of, and/or a particular

concern for, an at-home/family-based post-death

process — began offering their services publicly,

training others to support families in the same

way (Final

Passages in the U.S. being amongst the first

to do so), and even publicizing the necessary

information on post-death care on the web (see

our Resources in Canada

— Post-Death page — Legal

Information and Regulations, Resources

Elsewhere —Post

-Death Care information,

and our own PDFs on Basics

on Post-death Care At Home below).

Those who focus on post-deathcare support are

most often called home funeral guides — although

pan-death guides and thanadoulas also include

this support in the whole pan-death continuum

of their practice, and some death doulas may offer

post-deathcare as well.

(return

to top)

Why Consider an At-home Family-based

(Home Funeral) Option

What

is a 'Home Funeral'?

By dictionary definition, a

funeral is a ceremony, or group of ceremonies,

held in connection with the burial or cremation

of a dead person. It doesn't include

the other elements of care or documentation that

funeral homes provide (washing/dressing

the body, embalming, make-up added to the face,

Death Certificates, etc.).

(return

to top)

| Is

use of a funeral home necessary?

In our culture, dealing with a dead body is

considered both taboo and dangerous to the

health of the caretakers (although

this is only true with highly infectious diseases

— in which case, it is unlikely that

the deceased would have died at home).

Therefore, it has been assumed that only specially

trained professionals are capable of handling

a dead body. |

|

Most

people worry that their final days will be

filled with pain and agitation. Usually

the opposite is true. In the days

and hours before people die, they typically

spend most of their time asleep or resting.

It's rare for pain to get worse

or for distressing symptoms to appear. Most

often, the various body systems just gradually

and quietly shut down.

[From Virtual Hospice

article Dying

at Home — My father would like to die

at home. What can we expect?] |

In

fact, it wasn't until the early 20th century (and

after embalming was popularized in WWI, for soldiers

being returned home for burial) that dead

bodies were customarily moved into funeral homes

shortly after death. Until then

(and for tens of thousands of years

of our species' history beforehand), most

post-deathcare was done at home — perhaps

with the assistance of a local doctor or midwife;

but in any case, with the help of those in one's

community who had experience dealing with dead

bodies.

Practically,

caring for a dead body itself is not that different

from caring for the same person while they were

dying — and in fact, often much simpler (see

Basics

on Post-death Care At Home PDF below, as well

as Caitlin Doughty's "Ask a Mortician"

video "Are

Dead Bodies Dangerous?").

Especially if the Death Journeyer had dementia,

or another condition that prevented them from

doing any of their own care, it is likely that

the family caregiver has been doing equally extensive

and intimate care for them (e.g.

cleaning private parts) to what is required

by post-death care.

| Given

all of the above, it is quite possible for

family members, or a group of friends, to

do all of the post-death care — whether

the death journeyer has died at home, or in

a hospital or residential care facility —

with or without the support of a DWENA practitioner. |

|

Today

her greatest wish is that "dying might

become a community event again.... it would

be good to see it become a natural part of

daily life." [From

"The silence of

the dying" Sunday Times (PDF

article), on

Sara Douglass —

nurse and fantasy-writer

— on dying from ovarian cancer.] |

(return

to top)

Choosing

a casket

Most funeral homes carry

(or show) only a limited

number of less ornate caskets, and encourage the

family to choose from amongst their wider array

of more elaborate ones. By law, you

do not have to choose any of them, and can order

your own from another business. Most

funeral homes carry cardboard caskets (generally

used for cremation) — and even though

you are unlikely to see them in the showroom,

you have a right to buy one and decorate it according

to your wishes. Some cemeteries may

refuse to bury cardboard caskets; but with the

growing trend of green burials, they may be open

to doing so simply to build some PR as 'ecologically

conscious'.

(return

to top)

'A

la carte' Services

Some funeral homes may

be willing to provide one or two specific services

(rather than their usual full range

of care) if you choose to do most of the

post-deathcare at home. Of course,

that is not what their business is set up for.

However, particularly those funeral

homes focusing on simpler or less expensive services

may recognize that — as at-home post-deathcare

becomes more popular — they can provide an

important support service. For example,

if the Death Journeyer has a pacemaker, the funeral

home may be willing to remove it before burial/cremation.

In all likelihood, they would wash

and re-dress the body as part of that procedure,

but then might be willing to release the body

(with proper documents)

to be taken home for the 'lying in honour'/visitation

before burial or cremation. They might

also be willing to provide transportation services,

if you don't have a vehicle available that is

appropriate for transporting a body; or take over

the paperwork.

It

would be wise to contact the funeral homes in

your area, well in advance of the death, to find

out which ones might provide 'a la carte' services,

in order to avoid potentially uncomfortable negotiations

at the time of deepest grief. If you

have a DWENA practitioner locally available, they

may be able to provide information on which funeral

homes are most likely to offer 'a la carte' services. Your

hospice may also be helpful in finding supportive

local services.

(return

to top)

Comparative

costs of funeral home versus at-home post-death

care [Downloadable PDF]

Note:

the above table only uses two particular funeral

homes' prices (circa 2014, now more) —

two of the less expensive ones in B.C. Some

of the more expensive funeral homes will charge

higher fees for most of these items — possibly

more than double the prices given on the left

side of this comparison. It

is only intended to give you a very general idea

of the parallel cost of the most inexpensive funeral

home usage, as compared to 'Post-deathcare

by family at home '. You will

need to compare prices with funeral homes in your

own area. The 'Post-deathcare by

family at home ' column does not include any

fees or donations to a private alternate deathcare

provider, and neither column includes the costs

of the actual burial or cremation (which

will be variable depending on where you live;

and what kind of casket and burial plot you choose,

if choosing burial) or required taxes.

(return

to top)

|

Saying

goodbye Many

people find — despite some initial

concerns about the taboo against handling

a dead body — that continuing to care

for their loved one after death is a critical

part of accepting the death, alleviating

the shock/numbness (common

even if the death is expected), and

beginning to release the grief.

Hospitals

and residential care homes — now recognizing

this — may offer several hours for

the family to 'say their goodbyes' before

moving the body: and even some funeral homes

may recommend not calling them until hours

after the death. However, several

hours may not be long enough — and

simply 'saying goodbye' may not have the

same effect as the testament of love that

one gives when actually caring for the body,

hands-on, after death.

Many find doing post-deathcare for their

person to be very comforting —

and sometimes a deeply sacred act; and traditionally,

it has long been considered one of the final

acts of respect to the death journeyer.

|

|

AfterWards

Take her not from me.

Let it be this hand

Who wipes the folds of her flesh —

A final encore to fading days.

With each tender stroke,

May her seasoned soul unwind its threads

from this mortal coil.

With each grieving caress,

May her enduring love weave more tightly

into the whole of my being.

Take

her not from me,

Until the last essence of who she was

is

truly gone,

And I have captured only what she left for

me —

In this hand and heart.

Pashta

MaryMoon |

(return

to top)

|

Community

of Grieving

In Western culture, grief

can be very isolating. Especially

over the past century, we have lost many

of the traditions that our ancestors brought

from other cultures, which provided ways

of grieving within a community and/or ethic

setting. When we lose soneone

close to us, we often feel that we are losing

a significant part of ourselves — and

truly, our personal world has

changed. This can end up

creating unfathomable wells of grief —

that we ourselves don't entirely understand,

and may be afraid of delving into. We

tend to assume that no one else would understand

the depth — or kind — of grieving

we are dealing with, leaving us feeling

very isolated in our bereavement. And

out of empathy or embarrassment, we may

be worried about setting off a 'grieving

episode' in another mourner, by speaking

about our own feelings — so we don't,

and then inadvertently contribute to their

further isolation.

The

actual act of doing hands-on post-deathcare

tends to evoke tears, and stories, and even

humour — that cannot be held back;

and so become shared, while doing a particular

task together. In the process,

post-deathcare — done at home — can

also create a 'community of grieving

' that may last for years to come. Families

and friends have the opportunity to become

comfortable with sharing whatever element

of their grief is coming to the surface

at the time — creating a 'safe space'

to do so again later, one-to-one. They

are also more likely to visit the grave,

or where the ashes are spread, together

later; or plan other kinds of 'anniversary

of the death' events — continuing the

'community of grieving ' in whatever

way, and for as long as, is needed. |

|

...

our grief-stricken loved ones (are

left) feeling isolated, judged, misunderstood,

and alone. And though grief is deep and personal,

it is not meant to be experienced all alone. In

fact, families and friends who are able to

share their grief find they have gained a

depth to their relationship that would never

otherwise have been found. (The

Do's & Don'ts of Helping Others Through

Grief, April 14, 2012 by Dr. Christina

Hibbert -- see also Talking

with Children and Youth about Serious Illness) |

(return

to top)

|

Children

and Death Our

culture teaches us to protect children from

the reality of death. Children (particularly

younger ones) live in a world of

immediacy, action, and direct consequences

— not abstract theory. The

combination of their infinite imagination

and lack of habituation to 'basic life rules'

can result in children taking on responsibility

for the death — as if something they

did caused it (not obeying

a parent, saying something untoward to their

friend, etc.), or at least that there

was something that they could/should have

done to avoid it. They often

don't reveal this sense of responsibility

until much later in life (and

often initially, only to a counsellor)

— after they have carried the guilt

or shame of it through all of their developing

years.

In

fact, children are more likely to understand

death as a normal process — and NOT

take responsibility for it — if they

are allowed to be directly involved as much

as possible with the whole of the pan-death

process. This would include

direct contact with the death journeyer

before death and during the death vigil;

and then being involved (in

appropriate ways for their age) in

the post-deathcare of the body, decorating

the casket, and participating in the actual

burial and the funeral or memorial services.

|

|

...

even very young children can sense when something

is wrong within the family.... Children

who are shielded from the truth are likely

to worry, rely on overheard bits of conversation,

or make up something in order to make sense

of the unusual behaviours they’re observing.... Many

experts who work with children and youth believe

that young people are better able to cope

with situations if they know what is happening....

No matter how difficult a situation

seems, children and youth are remarkably able

to cope and integrate illness and death into

their lives.... Often families do not want

children to be around someone who is dying.

However, this avoidance may lead

to more questions and possibly some fears

developing about illness and the end of life.

Making death a natural part of

life for children and youth will help them

integrate this experience into their lives.

[From Canadian Virtual

Hospice article "Talking

with Children and Youth about Serious Illness"

] |

As

much as this may seem a very somber activity for

a child, they can take delight in the simplest

offerings to the Death Journeyer (before

and after death): and this allows them

to remember the death with joy, as well as sorrow.

This participation then also makes

it easier for them to take part in later commemorations

(one grandmother has her grandchildren

make flower wreaths at the anniversary of their

grandpa's death), and thus they can remember

the Death Journeyer with a sense of joyfulness

and peace.

Ecological

footprint of home funerals/community deathcare

Almost

all of the supplies needed for a home funeral/community

deathcare are either already in the home or can

be reused after the deathcare — therefore,

there is very little that need to be disposed

of. One supportive funeral director

told us that the disposables for one body, cared

for in a funeral home, equals two large garbage

bags — gloves, sheets, gowns, masks,

etc. For some families, committed

to ecology in the rest of their lives, the ecological

advantages of a home funeral/community deathcare

are significant.

(return

to top)

Basics

on Post-death Care At Home

The

many details of post-deathcare may seem overwhelming,

but it is simpler than it appears. CINDEA

has produced a series of short videos, shown below,

that demonstrate the primary steps of what needs

to be done (because "a picture

is worth a thousand words"). The

written instructions in the PDFs "Post-Death

Physical Care" and "General Timeline"

(below the videos) describe

the process in more detail.

Most Death Journeyers have a wider support network

than you may at first be aware of (friends,

faith communities, political/social-issue groups,

online communities,

hobby/interest groups, etc.) — and

those people may appreciate an opportunity to

help. There may also be a pan-death

guide or other DWENA practitioner available in

your area to guide you through the post-death

care. See our DWENA Practitioners page for Canadian Death Midwifery Practitioners, Death Doulas, Home Funeral Guides and Funeral Celebrants in each provinces..

Legal

requirements are slightly different in each province/territory.

The required

documents are usually only issued to the next-of-kin,

the designated Representative or power of attorney,

or (post-death) the executor,

or funeral homes — however, your local DWENA

practitioner may also have copies. CINDEA

provides links to sites where the family can access

most of those documents themselves, for each province

and territory — see our legal

information section. Your

local hospice society may be able to provide further

information, or contact

us if you need more help (CINDEA

may be able to provide some local information

or ideas on how to find it).

You

may want to do some but not all of the post-death

care yourself. There might be a funeral

director in your area who is willing to perform

specific tasks (such as transportation

or dealing with the paperwork), instead

of their full package of services. However,

it is unwise to just assume that this will be

possible — phone around to different funeral

homes to check beforehand.

Whatever

your choices are, please take

care of yourself, and commit to only as

much of the post-death care as you feel able and

willing to do.

CINDEA 's "Post-death Care At Home"

video series

[Click

here

for the page containing all the videos below (plus

some general information), or click on each thumbnail

below for a specific video.]

|

|

|

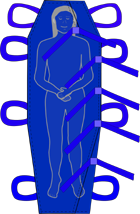

Part

1:

Moving the body |

Part

2:

Washing the hair,

face, and mouth |

Part

3:

Washing the body |

|

|

Part

4:

Dressing the body

Closing the eyes

and mouth |

Part

5:

Moving the body

into casket, or

Shrouding the body |

|

General

Timeline for

Post-death Care & Arrangements (PDF) |

Post-death

Physical Care (PDF) |

Click

here

to download the PDF,

which includes all of the following sections: |

Click

here to download the PDF,

which includes all of the following sections: |

| |

|

|

Well

in advance of the death |

| |

|

|

Just

before death |

|

Within

the first few hours |

|

Within

the first day or two |

|

Within

3-4 days (just before

the burial/cremation) |

|

Within

the next week to 10 days |

|

| |

|

|

Dealing

with the body

|

| |

|

|

Dealing

with rigor mortis |

|

Supplies

for post-death care |

|

Moving

the body |

|

Using

dry ice and gel packs |

|

Shrouding

the body |

|

The

National Home Funeral Alliance

(US) keeps an updated

list of podcasts. We also recommend

Donna

Belk on home funerals and How

to have a home funeral, and the "In the

Parlour" (trailer

available online) — as well as The

Art of Natural Death Care (Vimeo

online).

|

|

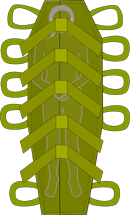

|

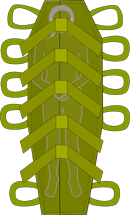

Mock

shrouding with queen-sized bedsheet and

four ties

|

(return

to top)

Shroud

Designs and Sewing Patterns

CINDEA

has provided 6 different designs for shrouds,

with graphic and written instructions. These

shroud designs have been approved for use at

the Royal Oak Burial Park Woodlands green burial

site (Victoria, BC, Canada).

It is possible that a traditional (non-green)

burial ground would accept a shrouded

body instead of a casket; and allow it to be

buried without a cement liner, because the ground

may not collapse over it. We

recommend that you

talk to your local cemetery about the use of

shrouds, especially if there is no green-burial

ground available in your area (see

Green

Disposition Options in Canada on our Post-death

page).

Click

here

to access all 6 of the downloadable patterns,

in PDF formats.

(return

to top)

Death

Journeyer's Remains

Note: further information is available on our

Resources

in Canada — Post-death page

and on our Greening

Death page (not completed

yet).

| If

choosing burial |

| |

|

|

Kinds

of burials |

|

Check

if any of your local cemeteries offer green

burials or hybrid burials (cement

liner on top, but not beneath — as

is traditional for Jewish and Muslim burials).

Also check what conditions they

require for the body and casket: for example,

a fully-green burial may not allow for any

metal on the body or in the casket —

either shrouds or caskets may be acceptable,

but both must be made from a biodegradable

material. You can check the

Green

Burial Council or the Green

Burial Society of Canada site for specific

areas in Canada where green burials are

available, or our Green

Disposition Options. |

|

Full-body

burial at sea is still theoretically possible,

and would be considered 'green' — but

because of strict regulations and the expense,

it is now virtually prohibitive in Canada.

[Note:

the only Canadian-based information we have

found on burials at sea — where the

whole body is given to the sea, instead

of scattering ashes — is at Burial

At Sea. Two companies

in the U.S.A. have made 'full body burial

at sea' possible -- Golden

Gate Burial Services, California, and

New

England Burial at Sea, east coast of

U.S.A] |

| |

| |

|

|

Requirements |

| |

|

You

will need to obtain a Permit for Burial

or Cremation (received from

Vital Statistics, and issued for free after

both the Medical Certificate of Death and

the Registration of Death are filed).

[see CINDEA's Post-death

Legal information and Regulations for

access to documents for your province/territory.] |

| |

|

If

you wish to transport the body yourself,

see the Legal

Information and Regulations on our Post-death

Resources page or apply to your local

provincial/territorial Consumer Protection

office to see if you require a Permit to

Transport the Body (these

may be available on-line). There

should be information accompanying the permit

to clarify what the requirements are for

transporting the body — including what

kinds of caskets can be used. |

| |

|

Prior

to burial (especially a green

one), there may be a requirement

to remove any pacemaker, prosthesis or other

mechanical or radioactive device (check

with your chosen cemetery in advance).

In the case of a pacemaker (or

any other internal artificial items),

you may need to have the body taken to a

funeral home to remove the device, unless

that has been done at the hospital (if

the death journeyer died there).

It may be difficult to get the

funeral home to allow you to then take the

body home — if you have problems with

this, please feel free to contact

us for suggestions on how to get official

support. |

| |

|

|

Cemetery

considerations |

| |

|

Green-burial

sites, and perhaps some traditional cemeteries,

allow for shrouds or cardboard or pressboard

caskets that can be painted by the family/friends

with biodegradable paints (check

your local art stores for which brand would

be best). |

| |

|

Some

cemeteries may allow the family/friends

to fill the grave — but if you choose

this option, make sure that enough soil

has been left by the graveside to do so.

Some may also allow the

family/friends to lower the body into the

grave — but paid employees will likely

need to be present for safety's sake. You

will need to negotiate with the cemetery

as to how they will supervise the lowering

of the casket — in order for them to

do so adequately, without interfering with

the burial ceremony. |

| |

|

Find

out if a representative of the cemetery

needs to be present at the graveside ceremony,

and negotiate with them re how involved

they are. |

(return

to top)

| If

choosing cremation |

| |

|

|

Kinds

of cremation

|

|

Regular

cremation (by intense fire)

is usually available and inexpensive. |

|

Open-air

cremations are traditional for some ethnic

groups (such as Hindus),

but are rarely available in urban areas

or even elsewhere in North America. There

is a movement to re-introduce them in Canada,

but we are not aware of any available at

the present time. |

|

Resomation

or aquafication (bio-cremation

— by chemical dissolving; also called

alkaline hydrolysis) has 20 times

less carbon-footprint than regular cremation. There

are only a few units functioning in Canada

at the present time, but likely to be more

in the future. [Note:

Promession

(freeze-drying) is also being developed,

but not available in Canada to our knowledge

at this time.] |

|

The

newest development is direct composting

of bodies, called recomposition

(intended for urban areas, but workable

elsewhere) — a project originally

referred to as the Urban Death Project and

now legalized in the U.S.A. as Recompose. It

is not available in Canada at the moment,;

but some of the next-stage of research is

being done here, and a facility is functioning

in Washington State (Seattle

times article on Recompose) It

has also been legalized in Colorado and

Oregon. |

| |

| |

|

|

Timeframe |

| |

|

In

most provinces/territories, a body cannot

usually be cremated — by law —

until 24-48 hours (usually

the latter) after the death; which

allows for a possible examination by the

coroner, etc., if deemed necessary after

the death. |

| |

|

|

Requirements |

| |

|

You

will need to obtain a Permit for Burial

or Cremation (received from

Vital Statistics, for free, after both the

Medical Certificate of Death and the Registration

of Death have been filed). [see

CINDEA's Legal

Information and Regulations for access

to documents for your province/territory.] |

| |

|

If

you are transporting the body yourself to

the crematorium, apply to your local provincial/territorial

Consumer Protection office to see if you

require a Permit to Transport the Body (these

may be available on-line or check our Legal

Information). There

should be information accompanying the permit

to clarify what the requirements are for

transporting the body — including what

kinds of caskets can be used. |

| |

|

Prior

to cremation, any pacemaker, prosthesis

or other mechanical or radioactive device

must be removed, because they are likely

to explode in the cremation chamber. In

the case of a pacemaker (or

any other internal artificial items),

you may need to have the body taken to a

funeral home to remove the device, unless

that has been done at the hospital (if

the death journeyer died there).

It may be difficult to get the

funeral home to allow you to then take the

body home — if you have problems with

this, please feel free to contact

us for suggestions on how to get official

support. |

| |

|

|

Other

considerations |

| |

|

It

may be possible to rent a regular casket

for visitation purposes, but the body will

generally be in a cardboard casket when

cremated (at present, a hard

container is required so shrouds can't be

used). If you choose

only the cardboard casket, it can be painted

(with biodegradable paints)

by family/friends. |

| |

|

Crematoriums

often have chapels where a service can be

held at the time of the cremation —

sometimes available free of charge. |

| |

|

Some

crematoriums may allow a family member to

push the button that starts the cremation

fire, and/or otherwise witness the cremation

— but you will need to specifically

ask if this is possible. There

may be an added charge for witnessing the

cremation and/or pushing the button, although

not necessarily. |

| |

|

|

Scattering

of ashes |

| |

|

There

are generally no laws prohibiting the scattering

of ashes (actually ground bone) by land, sea, or air — but

you should check the municipal by-laws.

|

| |

|

There

may be specific conditions for scattering

in public parks, or rules that ashes can

only be buried there — which then requires

a permit. |

| |

|

You

may need a special permit to scatter them

at sea (at least within the

national boundary). |

| |

|

Ashes

should never be scattered on private property

without permission (including

commercial private property — golf

courses, etc.). |

| |

|

Ashes

are usually scattered in a place significant

to the death journeyer or family; but it

is wise to remember that the use of that

land may change in the future (for

example, be dug up to build housing, etc.). |

|

Scatter the ashes over a relatively

large area. Too many ashes

in one small spot can kill the vegetation

above and around them — this includes

ashes in a biodegradable urn (see

Why

Burying Ashes is Harmful to the Environment) |

| |

|

|

Urns

for ashes |

| |

|

Generally,

1 pound body weight equals 1 cubic inch

ash |

| |

|

Unless

special urns are arranged in advance, the

ashes will come to you in one or two cardboard

boxes or plastic bags/tubs (depending

on the size of the death journeyer).

You should always check to make

sure that the box or bag is labeled with

the death journeyer's name, or some other

coding that ensures that you have the right

person's ashes. |

| |

|

Urns

can be made of almost any substance. Your

local funeral homes and crematoriums are

likely to have a wide variety. You

may wish to have an artisan friend make

one (or more) for

you, which may incorporate some of the ashes.

If you plan to bury the ashes

in a green-burial ground or a garden, the

urn will need to be biodegradable. [Note:

if you can't find a biodegradable urn locally,

see the Green Burial Council's page 'Find

GBC Provider' — at the bottom under

'Approved Products', check the pull-down

menu for 'urns'.] |

| |

|

If

you choose to bury the urn in a specific

piece of land, make sure that you have permission

to do so. |

| |

|

Your

family members may choose to divide the

ashes amongst them, as they may wish to

either each retain part of the ashes, or

scatter them in different places. Usually,

arrangements can be made with the crematorium

to have the ashes divided into several containers

(either cardboard boxes,

or pre-purchased urns or ones that you provide

yourself). Although holding

the ashes for a while can be comforting,

many families find that it then becomes

awkward to decide what to do with them for

the long term, and when to make that decision.

However, if the family wants

to scatter or bury them together, you might

want to pre-select a date — possibly

the first anniversary of the death —

to jointly make a decision as to the final

disposition of the ashes. |

(return

to top)

|